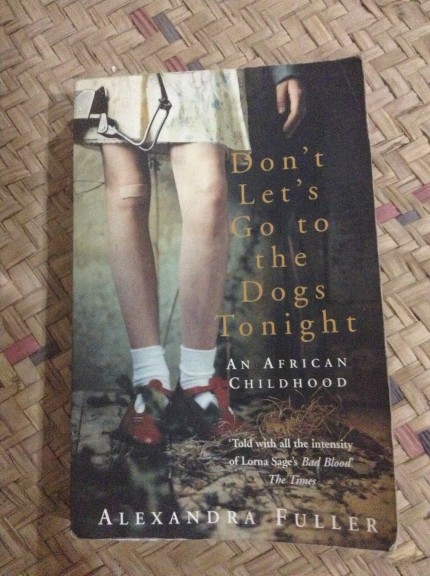

Boek | Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight

This is not a full circle. It's Life carrying on. It's the next breath we all take. It's the choice we make to get on with it.

In één week las ik dit boek twee keer. Ik vond het geweldig en genoot van de taal en de verhalen.

Alexandra Fuller beschrijft haar jeugd als dochter van witte boeren uit Engeland in de Afrikaanse landen Zimbabwe, Malawi en Zambia, precies de landen waar wij de laatste twee maanden ook in rond reden. Naast het familie-drama wat ze liefdevol vertelt, heb ik genoten van de kleine dingen uit het leven die ze in beeld brengt. Haar beschrijvingen zijn herkenbaar en hielpen me om dingen te zien. Bijvoorbeeld dat mzungus (witte mensen) niet langs de kant van de weg lopen, want dat doen de muntus (zwarte mensen).

Haar beschrijving van het klimaat op en rond het Zomba plateau is mooi en herkenbaar: "Zomba is built on the edge of a startling plateau on which the Life President has built himself a small palace (one of many scattered throughout the country) and which offers a sudden change of climate. The plateau, whose summit we reach by winding up an 'up'-only road (avoiding the lawless drivers hurtling illegally down) is planted with fresh, sweet-smelling pine and fir trees. Its ground soft and mossy; the air is thick and cool, and fresh with an almost permanent lick of mist. The dams and streams are stocked with trout; the roads on top of the plateau are hard, red, slick clay, which become so slippery during rains that our heavy truck slides drunkenly off their spines and into the ditch. Coming down the 'down' road from the plateau, the air thickens by degrees until, by the time we reach the town, we have almost forgotten the tonic of the plateau's summit, its cool, comforting. mossy silence." (p231)

Of deze typering van het door oorlog verscheurde Zimbabwe: "On the stretches of road that pass through European settlements, there are flowering shrubs and trees - clipped bougainvilleas or small frangipanis, jacarandas, and flame trees - planted at picturesque intervals. The verges of the road have been mown to reveal neat, upright barbed-wire fencing and fields of army-straight tobacco, maize, cotton, or placidly grazing cattle shiny and plumb with sweet pasture. Occasionally, gleaming out of a soothing oasis of trees and a sweep of lawn, I can see the white-owned farmhouses, all of them behind razor-gleaming fences, bristling with their defence.

In contrast, the Tribal Trust Lands are blown clear of vegetation. Spiky euphorbia hedges which bleed poisonous, burning milk when their stems are broken poke greenly out of otherwise barren, worn soil. The schools wear the blank face of was buildings, their windows blown blind by rocks or guns or mortars. Their plaster is an acne of bullet marks. The huts and small houses crouch open and vulnerable; their doors are flimsy pieces of plyboard or sacks hanging and lank. Children and chickens and dogs scratch in the red, raw soil and stare at us as we drive through their open, eroding lives. Thin cattle sways in long lines coming to and from distant water aand even more distant grazing. There are stores and shebeens, which are hung aabout with young men. The stores wear faded paint advertisements for Madison cigarettes, Fanta Orange, Coca-Cola, Panadol, Enos Liver Salts ('First Aid for Tummies, Enos makes you feel brand new')." (p105)

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight - Alexandra Fuller